This story is syndicated from West Side Story, the newspaper of Iowa City West High School in Iowa City, IA. The original version ran here.

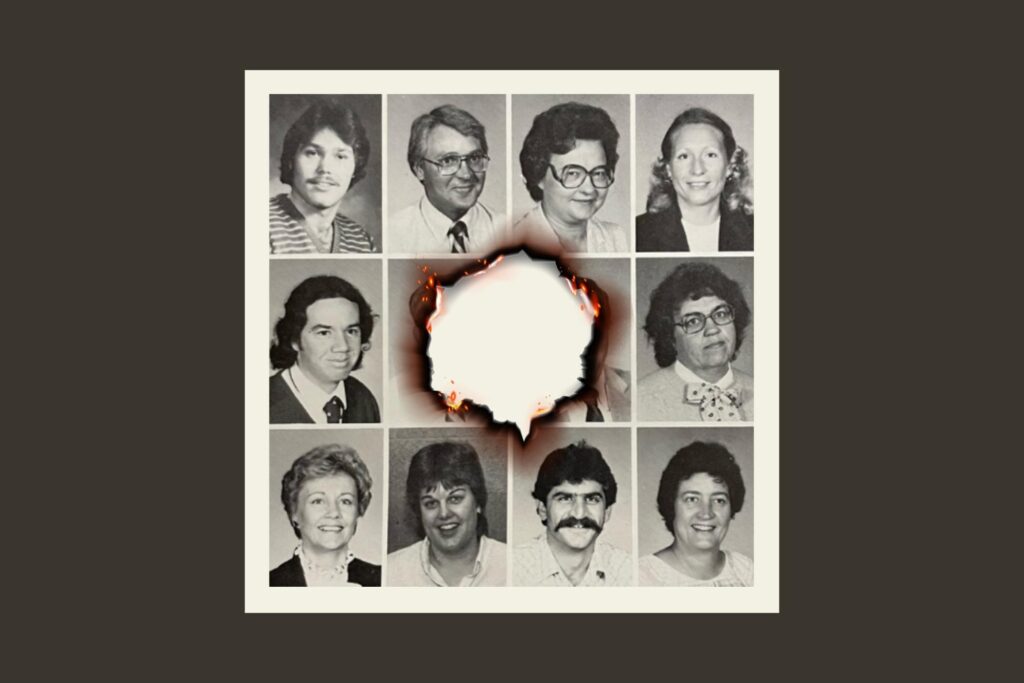

Across the country, teachers are finding themselves burnt out, prompting them to leave the field and adding to the national teacher shortage.

According to the World Health Organization, burnout is caused by three main emotions: a feeling of exhaustion, cynicism or apathy towards one’s job, which leads to reduced efficacy in one’s career. While burnout may affect any job, according to Gallup, K-12 educators have the highest likelihood of feeling burnt out — higher than in any other industry.

Paired with growing levels of burnout, increasing expectations of teachers lead them to leave the industry. Remaining staff members assume additional responsibilities, perpetuating the cycle. Advocates argue that the real shortage is not of teachers, but of the fair job conditions that would keep teachers teaching.

Travis Henderson, an AP Psychology and Government teacher and the Membership Chair of the Iowa City Education Association, has seen the district working to minimize teacher burnout. To combat burnout symptoms, the ICCSD works to build in more breaks throughout the year for students and teachers alike.

“[We] are trying to recognize the multiple cultures that exist in our community. That’s important, and it also gives teachers a pressure valve. The calendar committee in the districts called it a ‘humane calendar,’” Henderson said. “If we can create a more humane calendar, we can avoid burning teachers out. We can help them move from overextended back to engaged.”

University of Iowa student Noah LeFevre is a student teacher for AP United States Government and Politics and has already experienced one of the main forces driving teacher burnout: exhaustion.

“There’s a wide variety of things that can go wrong in [a] teaching career that add a lot of social work. You’ve got to have a big social battery because each day, you’re interacting and dealing with kids. Sometimes I come home, and I’m like, ‘I don’t want to talk to anyone right now. I’m done; I’m out,’” LeFevre said.

Henderson has seen how this fatigue can lead teachers to think that their work will never be finished.

“If you start feeling like you’re Sisyphus pushing a rock up a hill and never getting anywhere, you start to wonder if this is meaningful work. Then you start to feel cynical — and that’s when you go from overextended to disengaged,” Henderson said. “I get concerned when I hear my colleagues say things like, ‘I don’t think any of this matters.’ When they start saying those things, they’re trying to rationalize their exhaustion by disconnecting from the work.”

Although the ICCSD is making efforts to combat burnout, Henderson is still unsure if it will be enough. He feels lucky to be part of the district, though, because of its commitment to providing a quality work environment, he said

“We’re getting better at understanding how people burn out [and] why they burn out. We’re trying to help teachers feel a little bit better about the work,” Henderson said. “I feel bad for my brothers and sisters in districts that don’t pay very well because money is a stressor for everyone living in America right now. The research is pretty clear that you’ve got to pay people enough to take the issue of money off the table, so they can focus on all the other things.”

Henderson also teaches a University of Iowa pre-service class for individuals interested in receiving a teacher license and has noticed declining interest in teaching recently.

“When I started teaching that class, we had 78 students in it. This semester, we have 52,” Henderson said. “Some schools will be okay, but some schools are having trouble finding people who want to do any of the jobs, and they have open positions all over the place.”

According to Education Research Strategies, new teachers are leaving the profession more frequently than their more experienced coworkers. After the 2022-23 school year, 30% of teachers in their first or second year left their schools, while only 17% to 20% of teachers with eight years of experience left. Henderson has noticed older teachers seem to burn out less in their increasingly difficult work environments — he theorizes this is because they already feel effective and are confident in their ability to handle their work.

“A frog in water that’s slowly getting hotter won’t realize it’s getting hotter, but a frog that jumps into a boiling pot immediately jumps out of the pot,” Henderson said. “I feel like for younger teachers, the pot is already boiling, and it would be hard to jump right into it.”

Kailey Mgridichian, a West building substitute, first joined the district as a student teacher. After student teaching, Mgridichian was hired by the ICCSD as a district substitute teacher. While subbing, she saw the extensive early retirement plans offered to veteran teachers.

“I [thought], ‘There’s going to be so many positions open next year,’ but all these people are retiring, and the class sizes are [still] getting bigger and bigger,” Mgridichian said. “With the current political climate focused on misinforming and defunding education, I feel like a lot of teachers are going to leave because it’s hard to teach when people who aren’t teachers are trying to control our jobs.”

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds signed the Students First Act in 2023, which provided state education funding for K-12 students who choose to attend private schools. Over the course of four years, the state will spend about $879 million to implement this plan. With potential cuts to the federal Department of Education alongside changes to state curricula, some teachers worry their schools will not be able to keep them on staff.

LeFevre has noticed similar trends, noting that government intervention in teaching can intensify teachers’ inclination to leave the profession.

“The state government has been getting its hands in [the curriculum], which is an interesting dynamic. A lot of people going into education disagree with the way the state government’s running it,” LeFevre said. “All these factors coming together can create an environment [that people] get really tired of, and it causes them to want to do something else.”

While some specific, traceable feelings can lead to burnout, they don’t explain why teachers have been burning out now more than ever before. According to a survey from Merrimack College, 56% of teachers are “somewhat satisfied” with their jobs, yet only 12% are “very satisfied” with their jobs, a decrease from 39% in 2012. This lack of satisfaction often comes from the feeling that teaching has too many non-educational aspects, like managing requests and contact from parents and completing extensive paperwork. When teachers sacrifice their energy or health to get work done, symptoms of burnout are exacerbated. Mgrdichian often covers for sick teachers and notices the effort teachers put in, even when they stay home.

“I know teachers who are working on the weekends, teachers who are coming in at 7 a.m., and some kids don’t see that there’s a lot of passion and effort. It’s hard because if you don’t see it, you don’t know what’s there,” Mgrdichian said. “I see a lot in their sub plans because if… they wake up vomiting in the morning, they still have to write out sub plans. It’s a lot harder to take days off, so teachers tend to take fewer days off.”

Henderson has noticed that teachers increasingly get sick as their work piles up.

“Teachers start to lose sleep because they’re staying up to get work done, [so they have an] increased likelihood to get ill, miss work,” Henderson said. “One of the things we noticed after COVID-19 was an uptick in absenteeism amongst teachers. Some viewed that as teachers don’t have the stamina to get through the day anymore. I read it as teachers are legitimately getting sick more often because they’re stressed out.”

After the pandemic, 55% of educators were thinking about leaving the profession, according to a 2022 National Education Association survey. Five years later, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic still have residual effects. A RAND survey found that 40% of high-poverty school districts are bracing for cuts when COVID-era federal funding expires later this year, and many anticipate teacher cuts. However, even before COVID-19, current teachers were still feeling more burnt out than teachers had previously.

Henderson believes changing cultural expectations could be a contributing factor to more frequent burnout.

“Today, you walk through West High, and it’s a very diverse place, which brings a level of cognitive complexity that would not have existed for teachers working here in the ’90s,” Henderson said. “For example, I have to think about how my communication lands with different cultural groups. I have to make sure I’m being culturally sensitive in the materials I’m prepping. Different families expect different communication, so I have to engage in more communication systems to meet the needs of different families.”

Alongside increasing cultural expectations, technology has given parents more access to teachers and school curricula. Although Henderson doesn’t believe that more communication is inherently bad, he emphasizes that it becomes harmful when it distracts from building student-teacher relationships through the class and curriculum.

“There is ample research on what behaviors teachers engage in that have a really high effect on student learning. We need to focus on only asking our teachers to do the things that have the highest leverage on student learning: building relationships,” Henderson said. “I should close my computer, turn to the student and have a conversation about whatever exciting thing has run through their brain. Research says I will have a greater impact on them than whoever I’m going to impact writing that email.”

These issues have only been compounded by the perception of teaching as an easy job. Although LeFevre enjoys teaching, he recognizes that it can be intimidating.

“A lot of people view teaching as a profession that isn’t difficult, but if they do have the realization it’s difficult, that’s a first step to [leaving],” LeFevre said.

Senior Rana Saba has wanted to work with kids since she started babysitting around her neighborhood. Although she remains set on pursuing elementary education, Saba agrees that increased responsibilities are a concern when joining the education field.

“I feel like more has been put on teachers, there are more problems they have to deal with. Some teachers are more like counselors and do more than just teach kids, but [there is] also fun in that,” Saba said. “The job seems like there’s something new every day, and I won’t be bored.”

Sophomore Ella Krupp is part of Educators Rising, a nationwide organization that promotes and facilitates teacher preparation programs. West’s chapter meets weekly with aspiring educators from the University of Iowa to discuss careers in education. Discussions include topics like how high school students can prepare for studying education, goal setting and work-based learning. Krupp was especially interested in Educators Rising’s Grow Our Own program, which guarantees the student a job at ICCSD if they graduate through the program.

“I’ve always known I wanted to be involved in education past high school because I’ve always enjoyed [learning] in school,” Krupp said. “It’s also important to support the next generation of kids who are learning because it’s so important for the future of the world. We need to support learners and be good teachers for the kids who are going to come after us.”

In addition to her desire wanting to support future students, Krupp believes teaching is a great chance to make the world a better place.

“When you’re a nice person to other people, they’re also nice. I’ve had so many great teachers here at West who have inspired me to be that for other kids,” Krupp said.

Saba is also focused on doing something she loves rather than seeking the largest paycheck. Regardless of the challenges of teaching — including burnout — Saba is still intent on pursuing education.

“I like a challenge. Sometimes when I say I want to be a teacher, people [say], ‘Oh, good for you.’ We don’t get paid a lot, but it’s a lot of hard work,” Saba said. “With new policies, people are not wanting to be teachers as much, but that’s what I’ve always wanted to do, and I’m okay with however the system changes. I’m still willing to help educate children.”